Thinking Inside the Box

Harvard’s freshman orientation unintentionally divides students from day one.

Complex and fluctuating, an individual’s identity is not merely reducible to demographic characteristics outside one’s control. Rather, identity is an elastic concept encompassing fixed, inborn traits as well as talents, interests, ideas, and, most importantly, choices—characteristics that can change, or which individuals themselves can change, throughout their lifetime.

Days after I arrived on campus, however, Harvard sought to provide me with a radically different conception of identity. Freshman orientation is traditionally a time to become acquainted with one’s new school, to get to know one’s classmates and plant the seeds for future friendships. As one particular orientation activity made clear, however, Harvard’s approach to “getting to know” one’s fellow freshmen entails more than standard icebreakers; rather, the university appears to believe that becoming acquainted with others requires labeling them.

The university appears to believe that becoming acquainted with others requires labeling them.

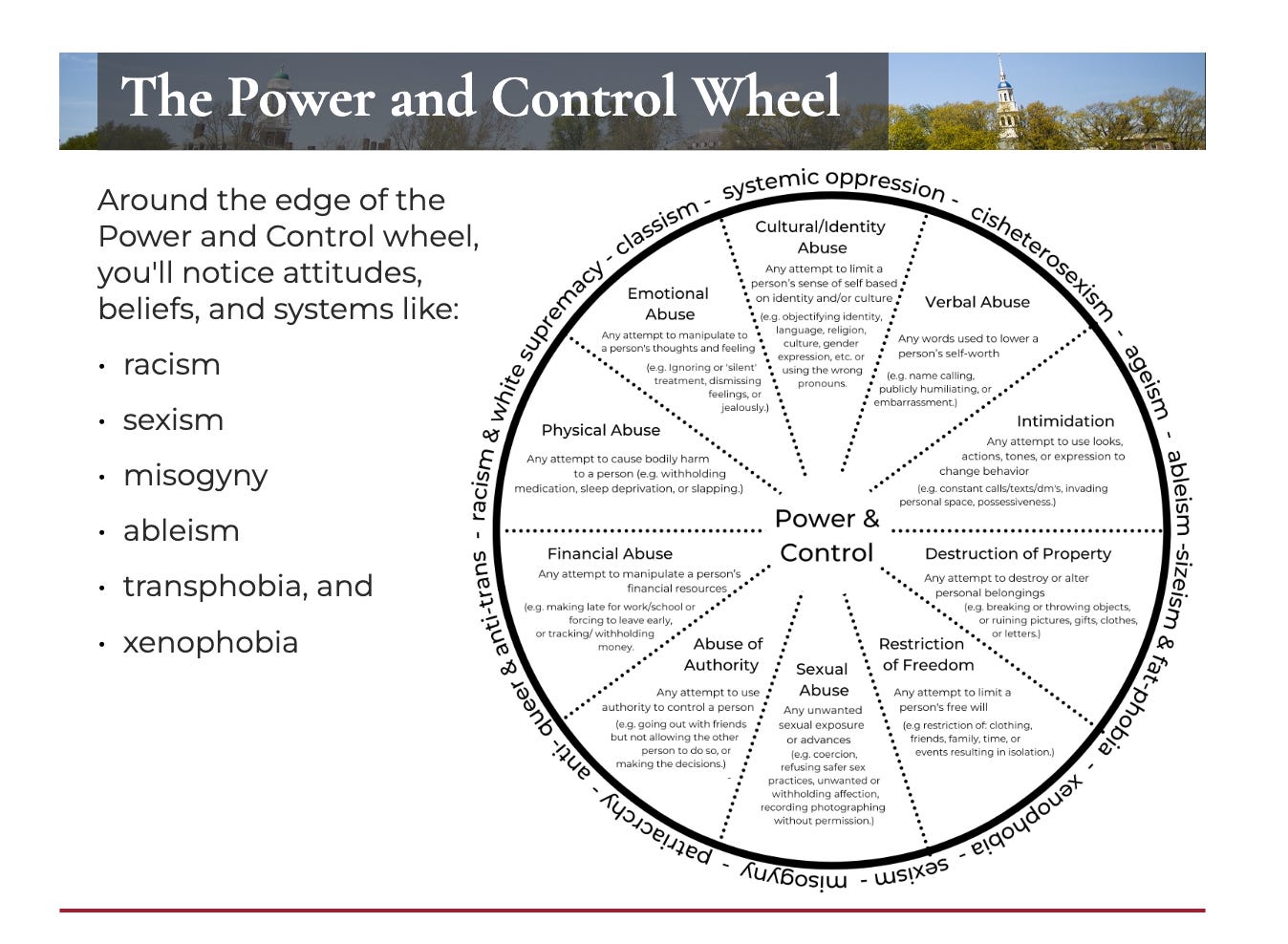

Our orientation leaders commenced this activity by dividing my entryway into small groups; perhaps they intended to create a comfortable environment for the decidedly uncomfortable exercise to follow. Waiting for the activity to begin in earnest, I anticipated playing a light-hearted game or taking an opportunity to reflect on our first days at Harvard. Unfortunately, I was quickly disabused of my naïve hopes. Our orientation leaders handed each of us a sheet of paper; in the center was a large wheel surrounded by eleven sections labeled: “race; ethnicity; socioeconomic status; gender; sex; sexual orientation; national origin; first language; physical, emotional, developmental disability; age; religious spiritual affiliation.”1 Next, our leaders instructed us to rate each trait on a scale from one to five according to three metrics: how much we value this characteristic, to what extent others judge us by it, and to what extent we judge others based on it.

Looking around, I was surprised to find that most of the students in my group had unquestioningly begun to construct their identity according to Harvard’s method. I was reluctant to comply, however, and my pencil was slow to touch my paper. By completing this exercise, was I agreeing to define myself by these eleven narrow categories? By completing this exercise, was I agreeing to view others through these lenses as well?

Scared of exposing myself—my true beliefs and identity—I admittedly caved. As I completed this task, allegedly aimed at promoting inclusion, I was overcome with a profound sense of isolation. Was I the only student who thought differently, who hesitated to define and thereby value myself by Harvard’s standards? Writing slowly, I nonetheless managed to complete the exercise, to lock myself and others into identity boxes, to tether human meaning and worth to thirty-three arbitrary numerical rankings.

Finally, the time came to put aside our pencils and discuss our ratings. Given the promptness with which my peers had started the activity, our conversation was surprisingly unnatural and tense. A few students mentioned the importance of their ethnicity or nationality, and one or two even shared a numerical rating; no one provided more than a cursory justification for their beliefs. Interestingly, more substantive conversations only began after we stepped away from our individual experiences and began speaking about identity in the abstract. Harvard’s attempt at encouraging us to express our personal identities, it seems, was largely unsuccessful.

Freshman orientation should introduce students to the numerous opportunities Harvard provides to improve and cultivate oneself, to shape and expand one’s identity. Instead, this orientation activity siloed freshmen into predetermined identity boxes through which to see and be seen. To define identity solely by these fixed traits, most of which are beyond one’s control, promotes further segregation and polarization in an already dangerously divided world. If Harvard wishes to promote a flourishing, cohesive community, our university cannot treat students as the sum of their demographic characteristics. By recognizing identity’s beautiful complexity and treating individual human beings as undefinable, Harvard can encourage friendship rather than prejudice, civil discourse rather than tribalism, exploration rather than close-mindedness.

What is my hope for the incoming freshman class? A community conversation that invites students to introduce themselves freely, without checkboxes, ranking wheels, or other arbitrary constraints. After all, a university education ought to encourage students to think outside the box, not to confine themselves to boxes.

ERINNA

A version of this article originally appeared in Freeing the Muses, the October 2023 print issue of the Salient.

“Inclusive Teaching – the Basics to Advanced Practices,” Inclusive Teaching at U-M LSA, 2023.

I would never send a child to Harvard. It is child abuse.

What a woeful, lowly state that once august institution has sunk to.

Bold move to write this down and share it. I cannot imagine the struggle to maintain your dignity in such a place.