Editor’s Note:

Many of our readers are likely aware that the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) recently ranked Harvard dead last in their annual campus free speech ratings. As part of those rankings, they also labeled Harvard’s free speech climate “abysmal.” This is unacceptable. The Salient is proud to add to the chorus of voices that have pointed out that valuable scholarship cannot be produced, nor can the education of “citizen-leaders” occur, when students and professors feel they cannot be frank with one another.

We hope our work serves to start the conversations that members of our community are otherwise afraid to engage in. Healing Harvard’s damaged culture of expression will require administrators and students to become less censorious, but it will also require someone to sincerely promote and defend conservative views. The Salient remains an outlet for that expression, and we hope those dissatisfied with the ideas and beliefs of the campus mainstream will feel emboldened both within and outside our pages to offer alternative perspectives.

We remain committed to the same mission we defined when we first launched this Substack: to reinvigorate thoughtful political and cultural discussion at Harvard through the presentation of conservative and otherwise unorthodox opinions. To this end, we will continue publishing articles from our print issues that analyze important social issues, both in connection with prevailing campus attitudes and in their own right. We will also redouble our efforts to shine a light on otherwise unremarked-upon campus events, initiatives, and student activities. As always, we undertake this work in a constructive spirit in the belief that our love for this university and the nation whose students it educates requires us to hold it to its commitment to Veritas.

With the fall semester underway in Cambridge, it is high time for us to recommence publishing on this platform. While the core of our mission remains focused directly on campus, we know that the support of Harvard’s alumni will be crucial in changing its culture. We also believe that Harvard’s leading role within American politics, culture, and business entitles those outside the Yard to know what is happening within her halls. As such, we remain excited to share our writing with a far wider audience than our print issues allow.

As a closing note, please allow us to offer our sincere gratitude to the donors, subscribers, and readers that make this work possible. If you’d like to join us in our mission, please consider subscribing and helping us spread the word.

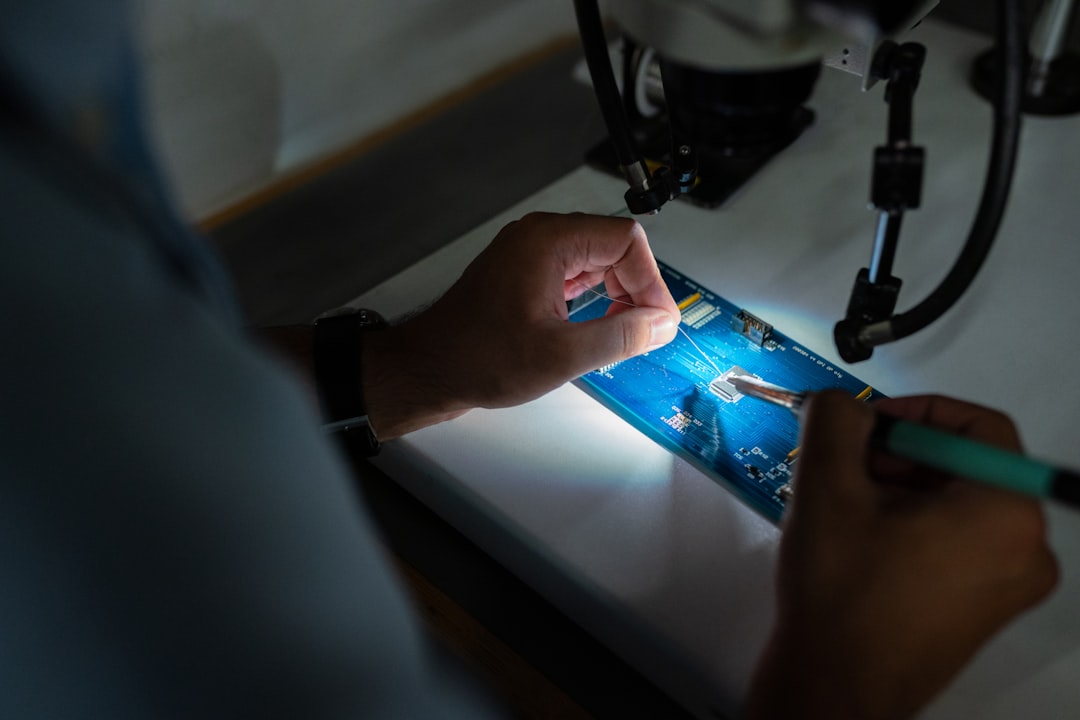

The study of engineering ethics has been on the rise since the Second World War. With the promulgation of codes of ethics and local and national boards to enforce them, as well as professional licensure, engineering is sometimes thought to be an entirely different animal than what it was in the 1940s. Engineering outside of research facilities was largely guided by heuristics and rules of thumb, and it was not until clearer expectations emerged as a product of the World Wars that engineering gained its current reputation as a particularly precise science. For example, manufacturing and construction were often flexible so long as a given job was effectively accomplished. Now, however, there are tolerances on everything from microchips to baby bottles; such standards, which define how much a product may deviate from its design, reflect the reality that imprecision can have catastrophic consequences.

Yet despite engineers’ apparent commitment to shaping new developments with clear ethical standards, ethical considerations are not much more impactful now than they were before the Second World War. We are continually reopening Pandora’s box; the speed of development is such that we barely sort out the mess left by one invention before the world is shaken up again. If the goal of engineering ethics is to curb ethical issues before they create scandal, it seems the field has failed. The attitude of most engineering fields is still one of ‘discover now, philosophize later’; scientists are still researching for the sake of research itself.

Countless examples illustrate the danger of this approach: the atomic bomb, napalm, domestic surveillance, bioweapons, miscellaneous methods of disseminating misinformation, and so on. The fruits of Progress are many, but so, too, are many of them rotten. Ever since the Manhattan Project, for instance, we have lived in a world which one mad leader or technical glitch can end. This kind of nihilistic predicament inspires hatred of both our past and our future. We see only one way out of the darkness: forward. We say, ‘Sure, there were days when things were simpler, but is simpler really better? Besides, how could we ever slow down? We would fall behind!’ But we were never in control. We are slaves to Progress, constantly playing catch-up with the latest breakthrough and with tomorrow’s new envy.

Of course, we usually dismiss this accusation and assert that we have control over our collective destiny. This is exactly what many institutions attempt to do, including Harvard’s SEAS1 through its mandatory hour-and-a-half engineering ethics session for all engineering students. The session is a two-part workshop; the first half is a rundown on some of history’s most egregious engineering failures that arose from falsified results and poor compliance with safety codes. Reviewing these mistakes was no different from the standard discussion of syllabi and honor codes at the beginning of every semester. The session leaders tried—but failed—to hammer home the point that cheating on your research paper can, instead of getting you expelled, kill people. The second part of the workshop involves practicing empathy by listening to other people’s opinions. This would have been a novel idea if we weren’t all accustomed to it from kindergarten.

Harvard and the rest of the Ivy League claim to empower students in their professional lives and to help them fulfill their unique potential, but I struggle to see how workshops telling us ‘don’t cheat’ and ‘be kind’ are changing anything. The Ivy League is empowering engineers, but to what end? I must ask whether Harvard’s efforts contribute to a restoration of technological development as a tool of humanity rather than a force we cannot control.

Simply offering more of Harvard’s current programming will not change the course of history, even if it successfully discourages students from using ‘oppressive’ language in their statistical reports—if indeed any would dare to do so anyway. I would not dismiss its efforts entirely, as there is something to be said for awareness of these topics, and admittedly my peers can often be concerningly oblivious to the effects of emerging technology. But this is all that engineering ethics covers, at Harvard and across much of the field: awareness.

The problem is not simply that we are unaware of the downsides of innovation but that we fail to anticipate them just as we fumble to address them in hindsight. No matter when an issue is discovered, we struggle to resolve it effectively because discovery itself is rarely unambiguously positive. Looking again at the Trinity Test that first successfully demonstrated an atomic weapon, we recognize that this experiment offered a much deeper understanding of nuclear physics and quantum mechanics. It was this very understanding, however, that enabled (even if it did not cause) great evil. This problem is not a unique byproduct of the desert sands of Los Alamos. It has plagued humanity for eternity: tools gave way to bludgeons, iron gave way to swords, machines gave way to catapults, cars gave way to tanks. As it turns out, the problem is not specific to engineering in the first place. The problem is perennial because it is the existence of evil.

Therefore, engineering ethics shouldn’t be about coping with engineering or trying somehow to ‘fix’ it; instead, ethical training should encourage engineers actively to address evil. Here is where awareness can become useful. What we need is an understanding of the challenges before us, one that makes us proactive in seeking ways to address them instead of avoiding them by arbitrarily hindering innovation or assuming that rules about honesty in data collection will suffice. The fact of the matter is that once the world’s next greatest weapon is within sight, it is only a matter of time before someone makes it a reality. The idea that we could undo the invention of the atomic bomb is naïve—but that should not preclude us from working to remedy its terrible effects.

While some students may find Harvard’s hour-and-a-half crash course through ethics useful, its effect is essentially negligible because Harvard does not invest in the personal moral development of its engineers. What’s needed is substantial advancements in that regard and a reconceptualization of invention as a moral act—to reshape engineering ethics in this way will be an extremely difficult task.

The moral compass of a technology will orient itself according to the field of social attitudes and assumptions it is placed in. If a society’s moral field is distorted, then its technological development will follow suit. Carrying the analogy further, a compass can be redirected if its immediate magnetic field is manipulated; so too can the engineers involved in a project make a conscious decision to break with convention and redirect its course. The strength of this influence is, ultimately, up to the innovators themselves. We need engineers to treat the power of creation with respect. While I would be wary of any program designed by Harvard to reshape its engineers’ moral intuitions, perhaps our university can at least remind them to listen to the ones they’ve got.

ARISTOPHANES

A version of this article originally appeared in Prometheus Now, the September 2023 print issue of the Salient.

School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

Yes, of course academics are researching for the sake of research itself. The idea behind research, and where it draws it audience from, is the creation of new knowledge. I am pretty sure new knowledge (if it could actually voice an opinion) would be agnostic with respect to morals.