The American worker is being replaced. Wherever possible, private equity firms and consulting companies are offshoring his job. When work must be done in this country, Silicon Valley is working day and night to build a robot to do it. Both groups are motivated by the same desire–to get the job done as cheaply as possible without worrying about pesky things like labor conditions. This is understandable on some level; everyone wants the best possible return when they invest. But the dispossession of our working classes cannot be ignored. Some enterprising politicians, recognizing this, think they’ve hit upon the solution: the universal basic income. To hear Andrew Yang tell it, the UBI will cure all America’s ills. In one fell swoop, it will end poverty and unleash an explosion of creative energy without significantly impeding the profit motive. The problem with both Yang and McKinsey is that they treat work as a fundamentally financial endeavor. Work is merely a process (and a disagreeable one at that) by which we trade time for money; automation is a positive good, so long as you don’t go hungry as a result.

Our managerial elites, probably because they themselves are burnt out on 100-hour weeks in the office or on the campaign trail, forget that work has value beyond paying bills. It is good for man to help provide for the well-being of his society rather than relying on its welfare to support himself. The former, rightly, provides a sense of pride the latter does not. In working, we make each other’s lives easier. When a worker is replaced by a machine, he loses more than his income–he loses in his coworkers and clients a key point of connection with his local community, the humility that comes from working for the benefit of others, and the sense of satisfaction that comes from doing it well. This is not to say that work is fun; it is to say that work is good for us. I may not like eating vegetables, but I do like being healthier as a result. This also perversely means that many of the people for whom UBI will do the most are those who most ought to be working. Yang and his acolytes are undoubtedly correct that many people, given UBI, will still find ways to be productive. But they must admit that UBI empowers the couch potato, especially after automation has made contributing meaningfully to society more difficult in the first place. Such people are about as likely to learn the value of work without the force of necessity as they are to eat a salad having been offered cake.

Many people already understand these ideas. However, while they may not suddenly become lazy, they are likely to become embittered by the loss of their livelihoods. A check from the government will not replace the sense of identity lost when one’s job disappears. This can easily turn into social unrest. What were the trucking protests in Canada early last year if not a reaction to that government’s attempts, via vaccine mandates, to forcibly unemploy people? This country, even more than our neighbors to the north, is imbued with a spirit of self-reliance. When our economic institutions begin to admit that blue-collar workers will not be able to support themselves and their families without government assistance, we can expect far more than a week of traffic jams. The idea that UBI will dissuade the no-longer-working classes from trying to punish Wall Street, Silicon Valley, and Washington for these economic changes is laughable.

Even if unrest can be calmed, these policies will not have the social benefits their advocates claim. The advocates of UBI argue that for every slacker it creates, so too will it empower a new creative endeavor. Is the next Shakespeare waiting to be freed from an assembly line? The principle of comparative advantage is just as foundational to modern economics as those principles by which automation is justified. If someone’s time was more efficiently spent creating art or writing or music, they would probably be doing so already.1 It has never been easier to get public attention for such things than it is right now. Furthermore, artificial intelligence programs designed to write and create art, even if they are not yet technically competent enough to compete with the best human artists, suggest that creative endeavors will not be spared from technological replacement. Automation also encourages a more rapacious consumerism. When we receive the fruits of another man’s labor–the sweat of his brow–we should be grateful for it even as we compensate him. In contrast, we don’t owe anything to the machines.

A check from the government will not replace the sense of identity lost when one’s job disappears.

We don’t owe anything to the machines–our economic decision-makers ought to remember that as they navigate the role of technological development in the job market. The robots have their place, but only where work is too dangerous or too difficult for humans to do unassisted. A program that helps doctors recognize early warning signs of disease is laudable; a kiosk that replaces a McDonald’s cashier is not. Insofar as UBI attempts to solve the problem of job loss due to automation, it will fail. We can't afford to sidestep the issue–it needs to be faced head-on. American businesses have already nominally abandoned their singular focus on shareholder value in favor of corporate responsibility initiatives. Instead of bizarre culture war salvos, the focus of such efforts should be helping the communities where they operate flourish. That starts with keeping as many well-paying jobs in human hands as possible.

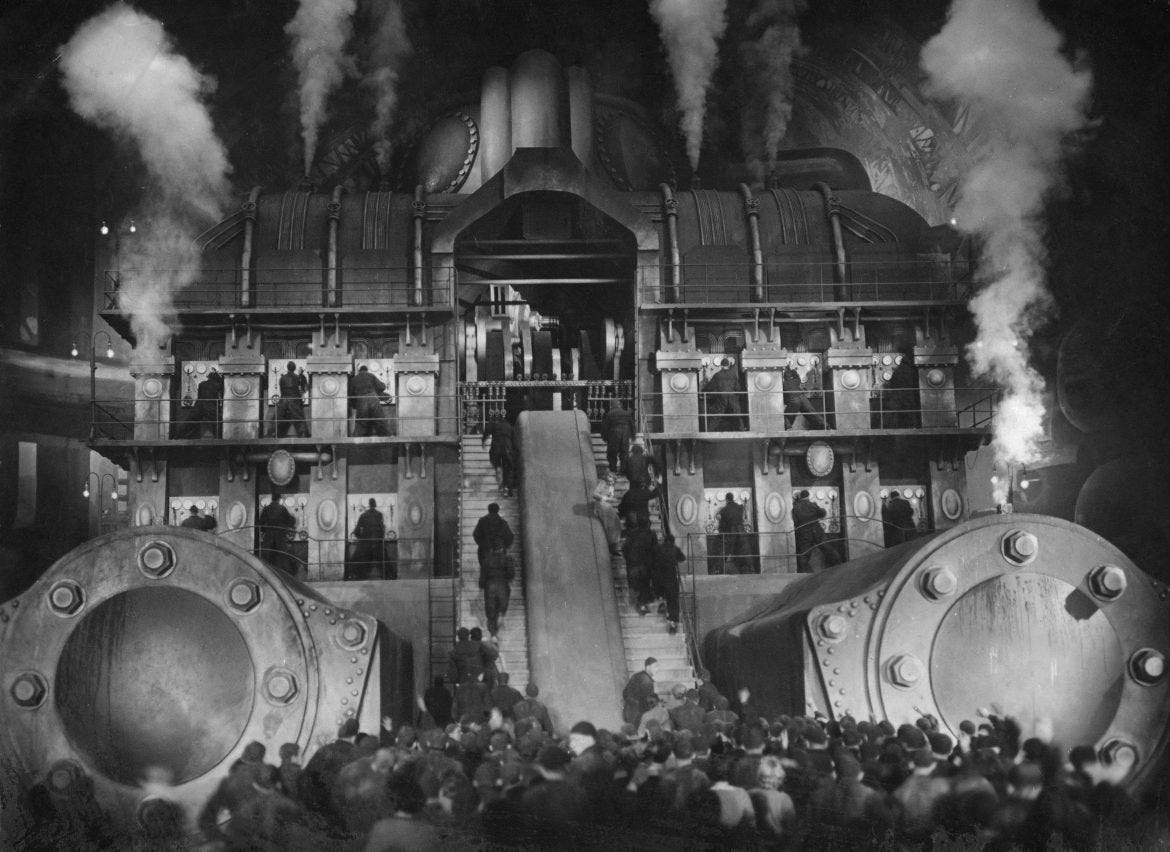

JOHN HENRY

A version of this article originally appeared in Works and Days, the April 2022 print issue of the Salient.

One notes that many of the celebrated authors and artists of the past not born into wealth made their earliest works, at least, while holding down other jobs.

This just in from forever: consumers want low prices. Kiosks replacing cashiers is a bad thing? Aldi's gets customers to return carts by requiring them to put a quarter in to get one which they get back when they return it. Should we stop this as well to protect jobs? In NJ, people are not allowed to pump their own gas. It "protects jobs."

To create more jobs, we should outlaw tractors and shovels and have people dig with spoons. (Thanks Milton Friedman.)

Let's get rid of combines so we can get back to the days of the small family farms.

The money we save because we can buy cheaply allows us to spend more elsewhere and create jobs elsewhere. The lump of labor fallacy needs to be learned by more people. This fallacy is cousin to tariffs to protect jobs.

Capitalist, corporate bootlicking nonsense. Time is money, and the more free time we have, the more ways we find to spend it. Assuming people will just sit on the couch for the next 50 years is silly. Utopia is when robots do the majority of the heavy lifting for us, with people either working 5-10 hours or not "working" at all. A life of leisure for all is the ultimate goal.